“At Newfoundland it is said that dried cod performs the office of money.” ~ Jean-Baptiste Say

In the cemetery at Cape Freels, Newfoundland, a weathered tombstone captures the remarkable story of John Ridout. Born in Bradford Abbas, Dorset, in 1793, John began life as a rural laborer. By 1812, he had deserted the Dorset Militia during the Napoleonic Wars, a choice that could have spelled disaster. Instead, he made his way to Newfoundland, where he transformed his life, becoming a respected member of his community. His journey reflects not only personal redemption but also the broader forces shaping the Atlantic world during one of history’s most tumultuous periods.

The Napoleonic Wars and Their Impact

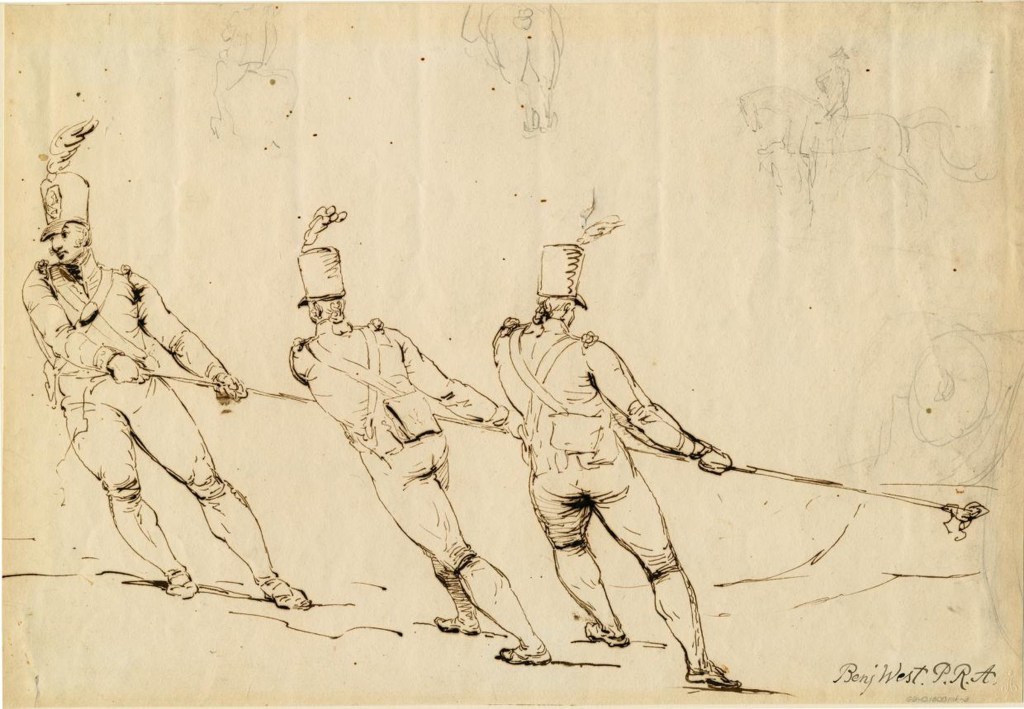

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a global conflict that engulfed Europe and its colonies. Britain, locked in a prolonged struggle against Napoleon’s French Empire, faced unprecedented demands on its population and resources. The British economy was heavily focused on the war effort, with industries and agriculture reoriented to support military campaigns. At the same time, a blockade imposed by France—the Continental System—sought to choke Britain’s trade routes and weaken its economy.

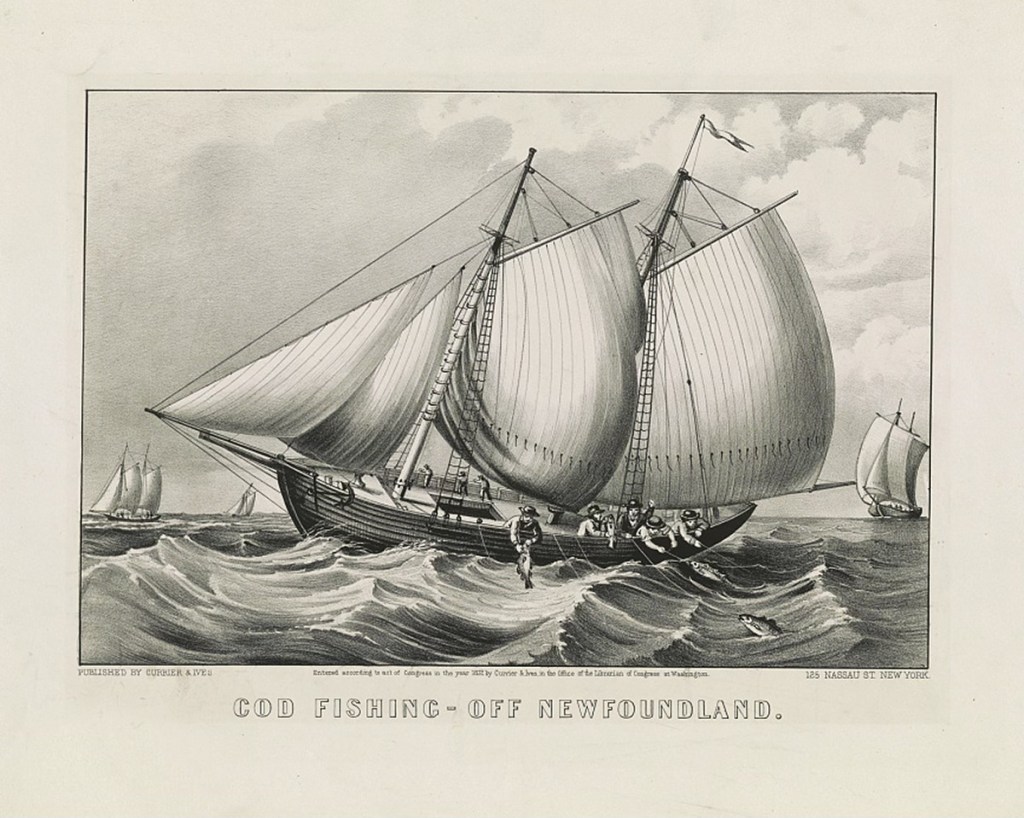

This disruption in European trade had a ripple effect across the Atlantic. With markets in Southern Europe and the Caribbean still accessible, Newfoundland’s cod fishery emerged as a vital link in Britain’s economic strategy. Salt cod, a durable and versatile food source, was exported to Catholic countries in Southern Europe, where dietary restrictions created high demand. The booming fishery provided much-needed revenue for Britain, even as war strained its homeland economy.

Why Men Deserted: John Ridout’s Escape

Against this backdrop, life in rural England was harsh. For laborers like John Ridout, economic opportunities were limited, and the demand for manpower in the military further destabilized communities. The militia, intended for home defense, was populated through a ballot system that forced men into service. While it was preferable to regular army duty, militia life was grueling, with low pay, long absences from home, and little chance for advancement.

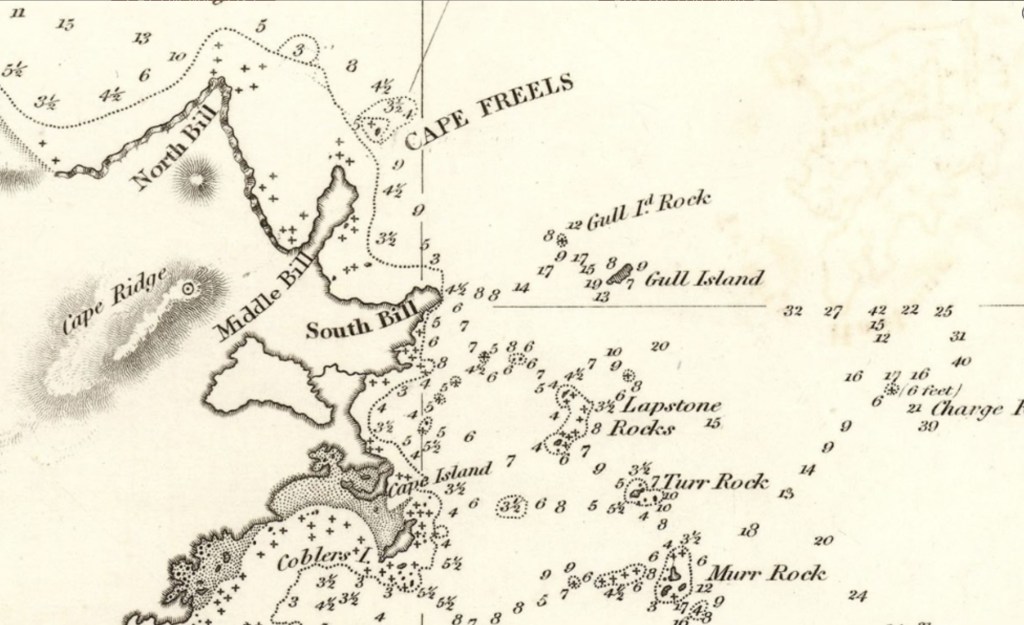

Desertion, though a crime punishable by death, became a desperate choice for many. For John and his brother Peter, the booming Newfoundland economy must have appeared as a beacon of hope and the possibility of freedom outweighed the dangers. For men like John Ridout, military service offered little incentive to stay. In 1812, at the age of 19, John and his younger brother Peter deserted the Dorset Militia and fled England, settling at Middle Bill Cove on the northern edge of Bonavista Bay and joining a growing community of English emigrants drawn to the promise of prosperity in the cod fishery. A newspaper report in 1813 described them as “supposed to be in Newfoundland,” providing a glimpse of their escape. The notice detailed John’s physical characteristics: 5 feet 4 inches tall, with dark hair and eyes, a round face, and a fair complexion. This description, intended to aid his capture, paints a vivid picture of the young man who risked everything to start anew.

Newfoundland’s Economy During the Napoleonic Wars

Newfoundland’s cod fishery thrived during this period, buoyed by Britain’s need for economic stability amid war. The fishery’s success was driven by a combination of geographic factors—proximity to rich fishing grounds—and economic necessity. With France attempting to disrupt British trade, Newfoundland became a critical supplier of fish to markets that remained open. The industry attracted workers from England’s West Country, including Dorset, Devon, and Cornwall, creating tightly knit communities abroad.

Life in Newfoundland was not easy. Harsh winters, grueling work on the water, and limited infrastructure tested the resilience of settlers. However, the promise of financial independence outweighed the risks for many, including the Ridout brothers.

Building a New Life

By 1819, John Ridout had married Mary Penny and begun to build a life in Cape Freels, Newfoundland. Over the next four decades, John contributed to his community as a member of the local road commission and an active participant in church life. His efforts helped shape Cape Freels, connecting its residents to neighboring outports and fostering a sense of cohesion in an isolated environment.

John’s transformation is memorialized in his tombstone at the Cape Freels United Church Cemetery:

“To the memory of John Ridout, a native of Bradford, Dorsetshire, England, and a respectable inhabitant of Cape Freels this last forty years, who died 22 March 1863 aged 69 years.”

The phrase “respectable inhabitant” underscores his redemption and the respect he earned over decades of hard work and community involvement.

Desertion, Migration, and Redemption

John Ridout’s story is emblematic of the broader patterns of migration and economic opportunity during the Napoleonic era. The war created upheaval, but it also opened new avenues for those willing to take risks. Newfoundland, with its thriving cod fishery, provided a rare chance for financial stability and community. For John, leaving England and deserting the militia marked the beginning of a journey that ultimately led to a life of respectability.

His story reflects the resilience of those who sought better lives abroad and the complex interplay of war, economy, and migration that shaped the Atlantic world during the early 19th century.

Personal details and descendants of John Ridout (my 4th Great-Grandfather)

Born: 1 Nov 1793, Bradford Abbas, Dorset, England to John Ridout (1770-1829) and Anne Napper (1769-1803)

First Marriage: before 1819 to Mary Penny (1803-1836) at Middle Bill Cove, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland

Children with Mary Penny:

- Rennie Rideout, b. 1819

- Susannah Rideout, 1822-1862; m. Jonas Humphries, 1800-1880

- Margaret Rideout, b. 1824; m. Thomas Stokes, b. 1820

- John Rideout, 1826-1903; m. Mary Ann Knee, 1831-1901 (my 3rd great-grandparents)

- Mary Rideout, b. 1830

- Peter Rideout, b. 1832

- James Rideout, b. 1834; m. Mary Martyn

Second Marriage: 21 Nov 1839 to Anne May Hunt, at Cobbler’s Island, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland

Children with Anne May Hunt

- James Rideout, 1840-1890

- Jacob Rideout, b. 1842

Died: 22 Mar 1863 at Cape Freels, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland

Burial: Cape Freels United Church Cemetery, Bonavista Bay, Newfoundland