How the Medley and Rawlinson Families Escaped the Lancashire Cotton Famine for a New Life in Massachusetts

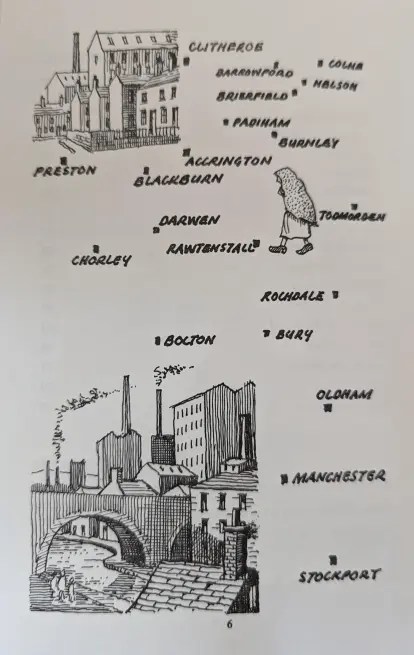

The story of my ancestors is woven into two continents and shaped by one of the most unexpected consequences of the American Civil War: the collapse of the British cotton industry. In the early 1870s, the Medley family of Oldham and the Rawlinsons of Chorley — both towns in Lancashire, England — left behind everything they had known. Their families had suffered deeply during the Lancashire Cotton Famine, a humanitarian crisis triggered when the war across the Atlantic severed the global cotton supply chain. In search of food, work, and a future, they emigrated to Lowell, Massachusetts, where the cotton mills of the United States were gaining power and momentum just as Britain’s were falling silent.

Boomtown Lancashire

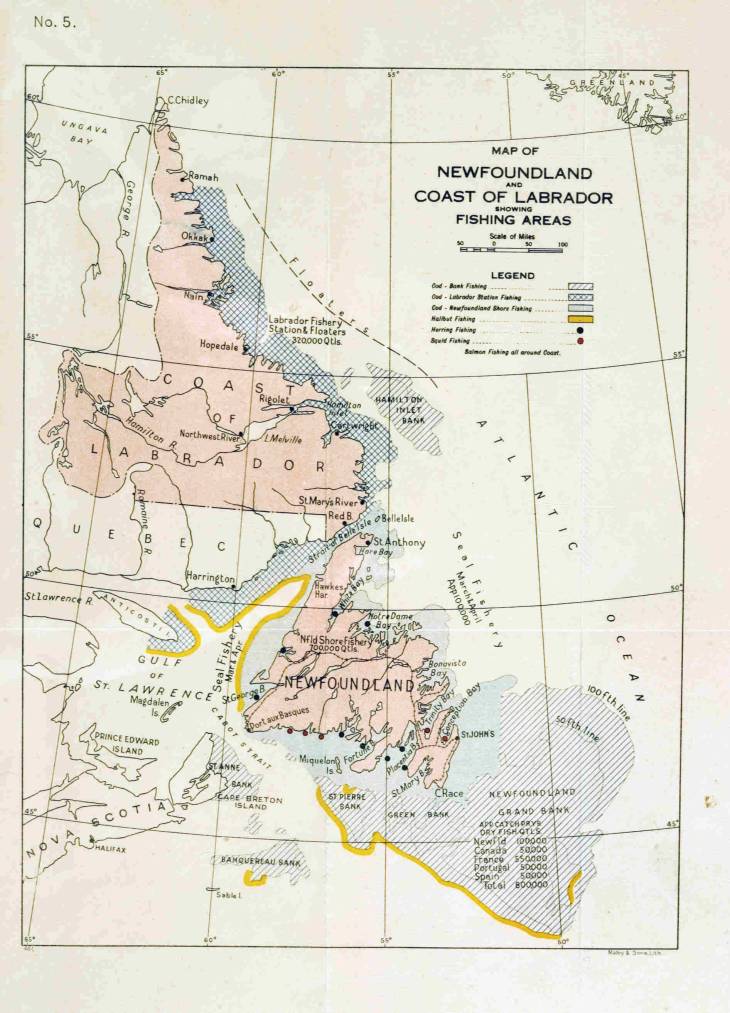

By the 1850s, Lancashire had become the industrial heart of the British Empire. The region thrived on cotton. It spun and wove raw fiber from across the globe into finished cloth that was exported to every corner of the British colonial world. Towns like Oldham, where the Medley family lived, and Chorley, home to the Rawlinson family, were part of this vast manufacturing network. More than 2,600 cotton mills operated across Lancashire, employing over 440,000 workers — many of them women and children.

The economy was strong, and work was plentiful. Families lived in modest comfort, supported by generations of textile expertise. For working-class families in mid-19th century England, Lancashire was a place of opportunity.

The Collapse: 1861–1865

But that prosperity came with a risk: dependence. Nearly 80% of the raw cotton used in British mills came from the southern United States. When the American Civil War erupted in 1861, Union forces blockaded Confederate ports, cutting off cotton exports to Britain almost overnight. What followed was a slow-burning disaster.

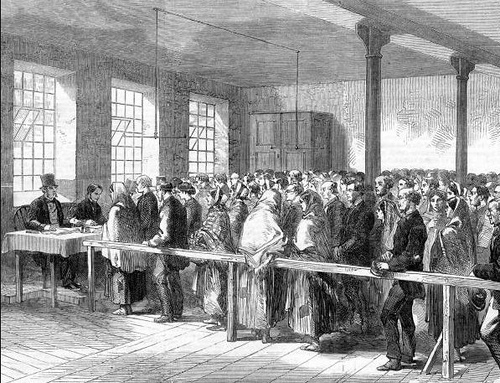

Mills began to shut down. Spindles stopped turning. By early 1862, hundreds of thousands of workers were unemployed. Whole communities were thrown into sudden poverty. This period became known as the Lancashire Cotton Famine — a term that obscures just how widespread and brutal the suffering was.

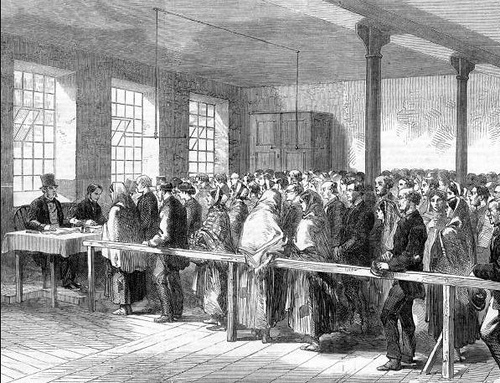

Local governments and charities tried to respond. Soup kitchens were opened. Sewing classes and public-works projects were created to provide relief. But these efforts were patchwork solutions to a global supply chain collapse. Reports from the time describe once-proud families pawning their possessions, burning their furniture to stay warm, lining up for food, and watching their children waste away from hunger.

The Medleys were among them. Two of their children died during this period — casualties of malnutrition in a country that, despite its wealth, could not feed them.

Shifting the Looms: America on the Rise

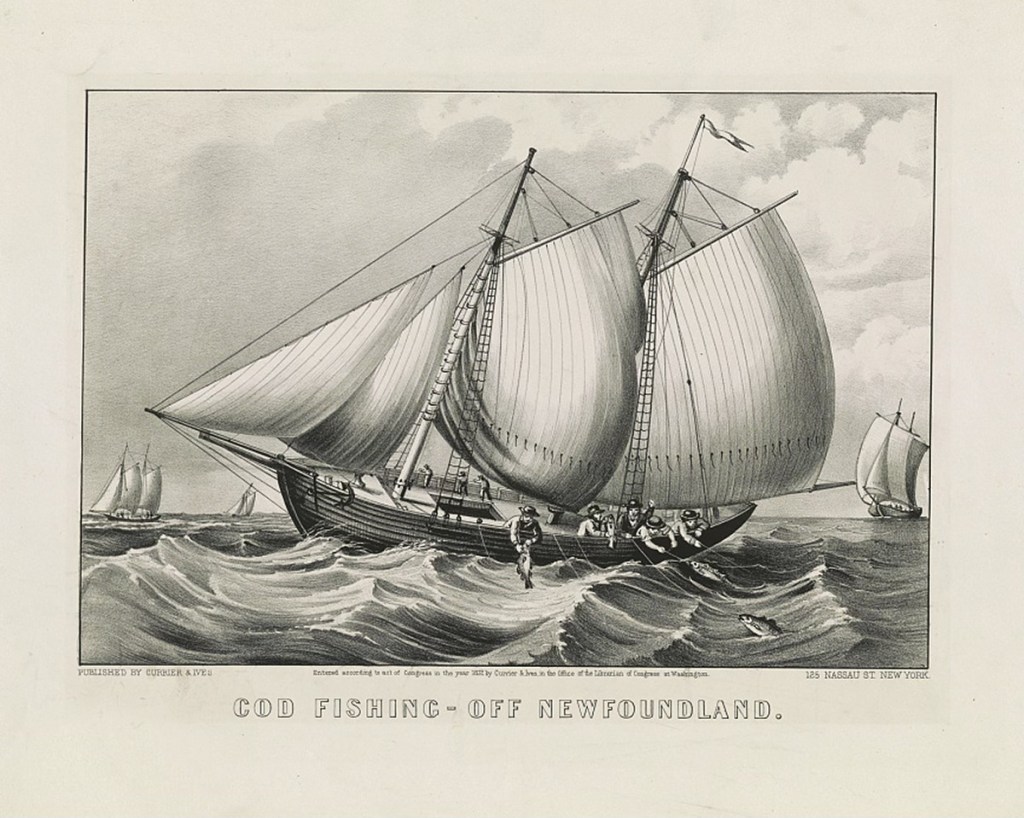

While Lancashire suffered, something else was happening in America. Though the South’s cotton fields were locked in war, the Northern textile industry — particularly in New England — was evolving. Towns like Lowell, Massachusetts, had long been home to early American mills, but by the 1860s and 1870s, they were growing in scale and sophistication.

Rather than depend on enslaved labor or imported cotton, the American North diversified its supply and innovated its manufacturing methods. The Civil War accelerated mechanization and infrastructure development. In the post-war years, the U.S. began producing its own textiles on a much larger scale — and it needed workers.

Mill agents scouted Europe, especially the skilled textile towns of Lancashire, for people who could operate the complex machinery of modern factories. They offered wages, housing, and the promise of a better life — and for many desperate families, it was enough.

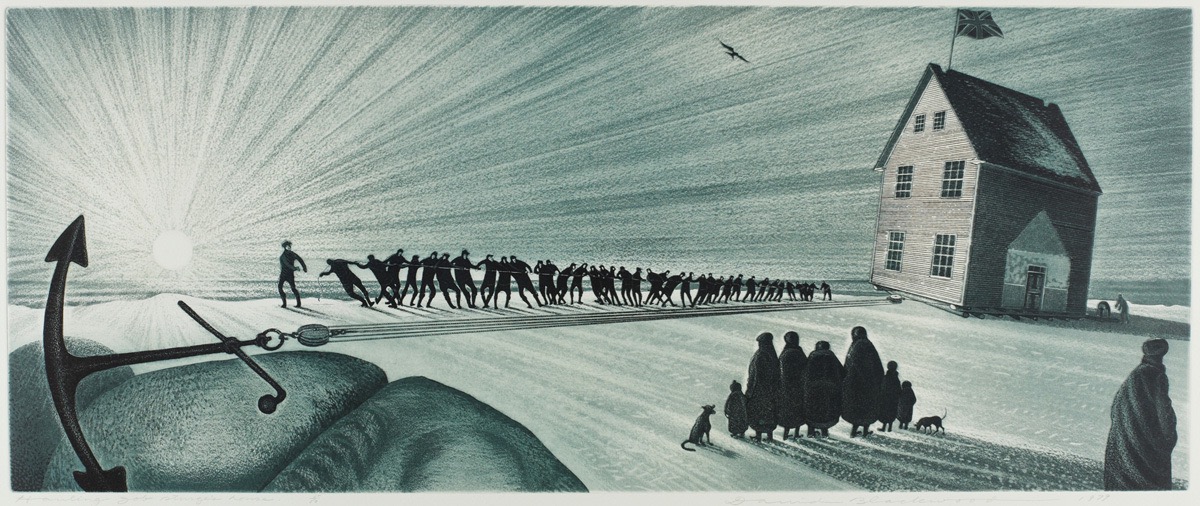

Leaving Lancashire Behind

The Medleys and Rawlinsons were among those who answered that call. With little left for them in England but loss, they boarded steamships bound for America. In steerage class, they made the crossing to a land they had only heard about — where cotton still spun, looms still turned, and children could grow up with more than a ration ticket.

In Lowell, they found steady work in the very mills that had, in part, risen due to the collapse of the British industry. Their skills translated, and they were able to rebuild. The irony, of course, is that their suffering during the Cotton Famine made them ideal candidates for the booming American textile economy.

Over time, they planted roots. Their names appeared in factory ledgers and U.S. census rolls. Children born in Lancashire became citizens of a new country. Their story — like that of so many working-class immigrant families — became one of resilience, adaptation, and renewal.

History often focuses on generals and governments, but it is also lived quietly — in kitchens without food, in decisions made out of desperation, and in the quiet courage it takes to start over. The Medleys and Rawlinsons carried not only their grief but also their expertise across the sea. In Lowell, they found work. In time, they found stability. And through their journey, they stitched their place into the fabric of a different kind of empire — one made not of conquest, but of survival.

Personal details and descendants of Gravelina Medley and William Rawlinson (my great-grandparents)

Gravelina C. Medley Born: 28 May 1855, Oldham, Lancashire, England, to Joseph Medley (1806-1873) and Hannah Chambers (1813-1886). Gravelina emigrated from Liverpool, England and arrived at the port of Boston on 01 December 1870. She traveled with her parents in steerage class aboard the Siberia. Died: 20 February 1920 at Lowell, Massachusetts — a victim of the Spanish Flu Pandemic

William Rawlinson Born: 12 August 1843, Bolton, Lancashire, England, to John Rawlinson (1815-1865) and Esther Manley (1815-1862). William emigrated from Liverpool, England and arrived at the port of Boston in 1871. He became a naturalized US Citizen on 24 October 1884 at Lowell, Massachusetts. Died: 24 July 1925 at Lowell, Massachusetts

Marriage: 14 March 1874 at Lowell, Massachusetts, USA

Children of William Rawlinson and Gravelina Medley:

- Lavina Rawlinson, 1875-1950; m. Irwin Leslie Prentiss, 1873-1926

- John William Rawlinson, 1877-1898

- Edward Ernest Rawlinson, 1879-1950; m. Bessie Kate King, 1887-1955 (my grandparents)

- Joseph H. Rawlinson, 1882-1906

Burial: Both Gravelina and William are interred at Edson Cemetery in Lowell, Massachusetts